Through the month of December, I had the privilege of working with Dr. Frank van Breukelen and his lab at the University of Nevada Las Vegas. I thought that Las Vegas would just be an odd collection of casinos and flashing lights. While there were a few of those, there was also an entirely separate side of the city that I fell in love with. For instance, the entire city is surrounded by mountains and there are something like 8 National Parks within a day’s drive!

Contrary to what it might sound like, I wasn’t there to pursue an alternative career to academia; I was there to study tenrecs! Tenrecs look like hedgehogs but are actually Afrotherians, meaning they are more closely related to elephants and aardvarks! (Look at their little tusks!) They’re considered “protoendotherms” and don’t regulate their body temperature as closely as other mammals. Frank and his team have a captive colony of breeding tenrecs living at the University of Nevada-Las Vegas, which makes studying them a lot easier than if I had had to travel to Madagascar!

Tailless tenrecs, Tenrec ecaudatus, are heterothermic endotherms endemic to subtropical Madagascar. They have one of the lowest body temperatures of any eutherian mammal and have evolved to survive at ambient temperatures close to or above body temperatures. The goal of my G2P2POP RCN-funded exchange was to compare tenrecs, an oddity by mammalian thermoregulatory standards (because of their flexible body temperatures), to other species’ known thermoneutral zones by using flow-through respirometry and implanted data loggers.

All mammals are endotherms, meaning they produce their own heat and are thus able to maintain body temperatures elevated above ambient temperature. However, not all endotherms are homeotherms, animals that actively defend constant and high body temperatures. Instead, many endotherms are instead heterotherms, and vary their body temperature with changes in ambient temperature, rainfall, or food availability, saving them a vast amount of energy that can then be in reproduction or immune responses. A core part of my Ph.D. research focuses on this heterothermic-homeothermic continuum, specifically quantifying where on the continuum different species fall and why those species have evolved to be at those points. Perhaps the most exciting species I could possibly study would be these tenrecs because as protoendotherms, they could be one of the most extreme heterothermic mammals and represent one end of the heterotherm-homeotherm continuum.

The great thing about being in Las Vegas is that Sable Systems International, the company that makes the oxygen analyzers and pumps used for respirometry (and the company I had frantically emailed to help me troubleshoot from the field many times), is just a short drive away! It was also pretty rad meeting Barbara Joos, the woman who helped me incredible amounts during my field seasons during the last two years!

With the help of Dr. Marshall McCue, we used a Sable Systems PromethION flow-through respirometry system at Sable Systems International to measure oxygen consumption, and water vapor and carbon dioxide production. The fantastic thing about the PromethION was that we could test 16 animals at a time! This meant that in two days I was able to collect as much data as I had collected during my two months in the field! It also helped that I didn’t have to catch the tenrecs in a jungle every day. (I also learned the joys of working with captive animals– they don’t bite as much). Each test was 8 hours long and consisted of one ambient temperature. We conducted tests at a range of temperatures from 12 to 34°C.

Respirometry allows researchers to quantify the amount of oxygen an animal is consuming and how much carbon dioxide and water vapor and animal is expiring. These rates of gas exchange are common proxies for an individual’s metabolic rate. At high temperatures we expect animals to increase their metabolic rates as they lower the body temperature by panting or sweating. At lower temperatures, we expect animals to either increase their metabolism as they attempt to defend their higher body temperatures or save energy by lowering their metabolism and lower their body temperature to around ambient temperature. In between these two extremes, most animals have what we call a “thermoneutral zone,” or a range of temperatures between which they don’t have to spend extra energy to maintain a constant body temperature. The upper and lower limit of this range has not yet been defined for the common tenrec and one of the thermoregulatory parameters we are hoping to quantify through our project.

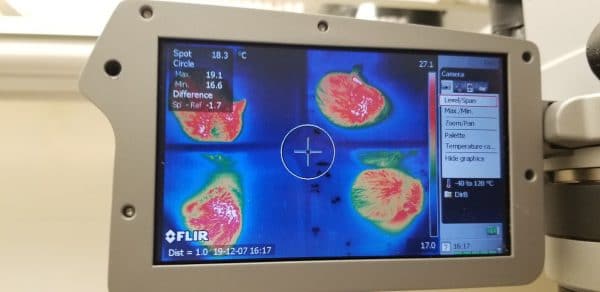

We also identified and quantified their thermal windows (areas of the body that dissipate heat via increased vascularization and surface area) using thermal imaging. I stood in a temperature-controlled room with the tenrecs and took photos of them with a thermal imaging camera every 5 minutes while they did their job and adjusted to the new ambient temperature. I started each trial at 20°C and from there either raised or lowered the temperature every 90 minutes. For the cooling experiments, I lowered the temperature to 18 and then 16°C. And for the warming experiments, I increased the temperature to 24, 28, and finally 32°C. It was funny to watch them adjust their position to either very warm or cool temperatures because I realized I was making the same changes; when the temperatures were colder, I was keeping my hands in my armpits and trying to reduce my surface area to volume ratio, and a few feet away the tenrecs were also curled up and tucking their paws under them to stay warm.

We expected tenrecs to have higher metabolic rates at the lower and higher range of temperatures that we tested them at, but instead saw very “hard to discern patterns” that we have yet to make sense of. At low temperatures, individual tenrecs fluctuated between relatively high and relatively low metabolic rates throughout the experiment. More surprising yet, was that preliminary analyses show these changes in metabolic rates are not correlated to changes in body temperatures. At cool ambient temperatures, animals with higher metabolic rates did not necessarily have high body temperatures and animals with lower metabolic rates did not necessarily have low body temperatures.

These preliminary results further highlight how, after decades of research into thermoregulation, we still have so many unanswered questions. It really is an exciting frontier of physiology!

Collecting comparable physiological data on a novel species contributed to our lab’s dataset of mammalian thermophysiology measurements, which is currently lacking in tropical and subtropical mammals. Through my work with Dr. van Breukelen, I learned new lab-based thermophysiology techniques and gained experience with Sable Systems’ technology. In addition to these new techniques, I also got first-hand experience recording and analyzing the thermophysiology of a protoendothermic mammal, and because of its unwillingness to follow “normal” physiological rules, I have been forced to reevaluate my definitions of what I used to consider standard physiological definitions.

I would like to express my deepest gratitude to all the people who made this exchange possible and successful! Thanks to Frank and Michael for helping me become more confused by tenrecs and more familiar with all the previously assumed physiological rules that they break. Thank you to Gilbecca, the queen tenrec wrangler and her fantastic troop of undergrads keeping all the tenrecs happy and ready for their daily field trips. Thank you to the crew at Sable Systems, especially Marshall, for getting us going on the PromethION System and being just as bewildered and excited as us by the data we collected. And finally, I am grateful to have received funding for this project through the RCN’s laboratory exchange. I can’t wait to share what we found!